When I’m asked by senior leaders about technology transformation, I recommend creating a learning organisation through an accountability culture. If an organisation doesn’t have accountability, it won’t learn from itself, and it won’t improve itself. The Accelerate book by Dr. Nicole Forsgren et al proved that the key predictor of better business outcomes is a learning organisation – fast, visible feedback loops based on people actively sharing information, and treating events as learning opportunities.

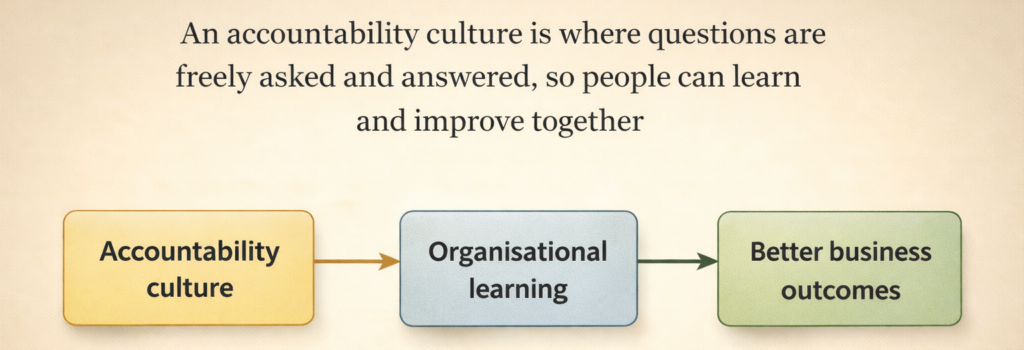

Learning depends on accountability. I’d say that accountability is answering questions, being accountable means theoretically having to answer questions, and being held to account means actually having to answer questions. An accountability culture is where questions are freely asked and answered, so people can learn and improve together.

I’ve worked in multiple high performing organisations, and each time there was an accountability culture. As a technical lead at LMAX under Dave Farley, anyone could question my design choices, and I could answer them. In addition, I could question Dave’s choices for the whole trading exchange, and he always took the time to explain his thinking. That’s what accountability looks like.

What unaccountability looks like

I often see an unaccountability culture in organisations. People don’t ask questions, don’t answer questions satisfactorily, and/or don’t follow up on answers. Here are some examples:

- Mandatory AI adoption. A CTO announced mandatory Cursor adoption for engineers. After three months of mixed AI experiences, tech leads asked about value for money. The CTO’s only answer was productivity had to increase.

- Product away day. A CPO ran an away day for their senior leaders. A few attendees skipped the pre-reading, and their catch up time cost everyone half a day. The CPO didn’t ask why those attendees had come unprepared.

- Website outage. A COO endured a multi-hour website outage. They asked their head of operations why the outage happened. The head of operations only gave cursory answers, which the COO had heard before.

- Under-performance. A CDO had a head of data engineering, head of data science, and head of analytics as their direct reports. The head of analytics was known to be under-performing, but the CDO didn’t ask them about it.

Unaccountability happens for lots of reasons. Sometimes people can’t speak up because of power dynamics and systemic inequalities. Sometimes they’re constrained by insufficient capacity, knowledge silos, vague responsibilities, and skill gaps. But the overwhelming reason I see is people prioritising niceness over kindness. We’re socially conditioned to avoid discomfort, and preserve relationships and status. We over-estimate the danger of speaking, and under-estimate the cost of saying nothing.

What unaccountability feels like

I think about the negative impact of unaccountability at three levels:

- Personal. People are left frustrated, disillusioned, and upset, because when efforts to collaborate, learn, and improve go nowhere it shows that opinions and time don’t matter. In the CPO away day example, the prepared attendees were resentful of the unprepared attendees for the extra effort they’d put in, and it damaged relationships.

- Cultural. Inaction is understood to be safer than curiosity, because when saying something doesn’t make a difference, silence becomes the norm. Seeing the CPO not ask questions signalled to attendees that unpreparedness had no consequences, and curiosity was unnecessary.

- Organisational. Learning doesn’t happen, because when feedback loops are missing or broken, decisions aren’t examined and experiences become waste. When the CPO didn’t ask why some away day attendees were unprepared, they missed a chance to learn their product leaders regularly worked out of hours on unsustainable client demands

Unaccountability compounds over time, because people copy power. When they see unasked questions, unsatisfactory answers, and unactioned follow-ups from their senior leaders, they adapt downwards and standards decline. High performers lose their gumption, and low performers are emboldened. The same problems repeat, and the same flawed solutions are started from scratch. If an organisation doesn’t have accountability, it won’t learn from itself, and it won’t improve itself.

Start accountability where you are

Accountability builds personal, cultural, and organisational norms. And as usual, change starts with the mirror. I suggest:

- Ask obvious questions, even when they feel awkward

- Take answers seriously, and ask clarifying questions to show you are listening

- Follow up when you say you will, especially when it would be easier not to

I saw Dave Farley consistently model these behaviours at LMAX. Senior leaders create accountability cultures when they recognise that their actions have a disproportionate influence, and they have a responsibility to set the standard – because many people can’t or won’t speak up until leaders do.

Assuming that people need your help to prioritise kindness over niceness, by asking and answering questions openly, is a good place to start. It can feel uncomfortable. But in my experience, navigating a tricky conversation to learn together creates deeper trust and stronger relationships, as well as organisational learning. I’ll continue holding myself and others to account, and teaching other people how to do the same – accountability is at the intersection of my personal values, and it defines who I am.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone who holds me to account, including Rupa Kotecha-Smith, Alun Coppack , Bethany Pascoe, and Liz Leakey . Thanks also to Accelerate by Dr. Nicole Forsgren et al, Crucial Accountability by Kerry Patterson et al, Unaccountability Machine by Dan Davies, and Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance by Robert Pirsig.