A while ago, a media customer asked me to assess their search team. They’d been told to adopt Continuous Delivery practices, while still shipping features. The team struggled to make changes, deadlines were missed, and morale was low. I sympathised, and could see most of the pain was self-inflicted. Other teams had successfully adopted Continuous Delivery, but the search team had started from scratch. Their manager asked me “are we in chaos”, and were surprised when I said “it’s repeated complexity not chaos, and the repetition is the frustration”.

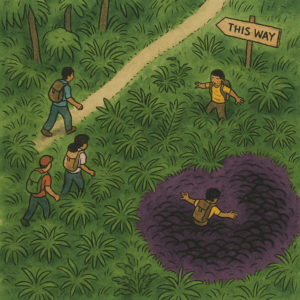

The Cynefin framework is helpful here. In chaos, cause and effect are unclear, and the environment is unstable. An analysis won’t work. You have to act to create order, sense what’s changing, and then respond accordingly. If you’re in a jungle and it’s on fire, you get out.

In complexity, cause and effect is only understood in hindsight, and the environment is dynamic. A step by step plan won’t work. You have to probe the terrain, sense what works, and respond by adapting. If you’re in a jungle, you gradually hack through the undergrowth. If enough people take the same route, a trail starts to form. That’s how learning happens.

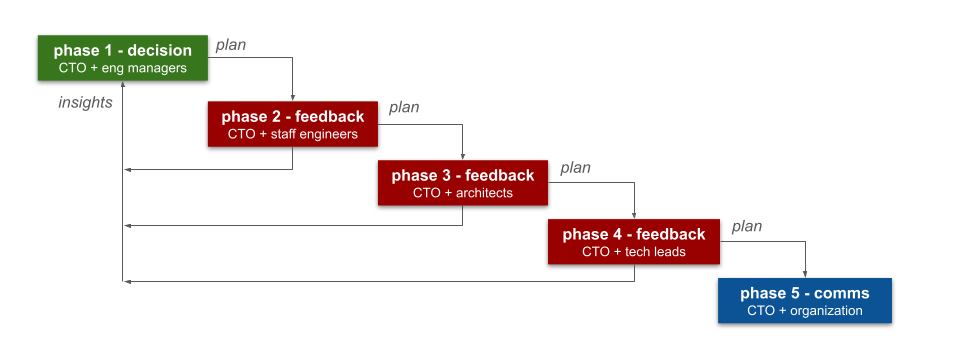

Over time, I’ve realised this is my leadership style. To help teams navigate complexity by finding a way through, capturing what we’ve learned, and sharing it so others can go further and faster. That’s principles to guide us, practices to ground us, patterns to repeat what works, and pitfalls to avoid what doesn’t. When I was a full-time engineer, I built CI/CD pipelines for teams. Then I created paved roads in platform engineering. Now I write advisory guidelines in inner-sourced handbooks, that anyone inside Equal Experts can use and improve.

Back to the media customer. Their search team was frustrated, and frustrating, because they were ignoring the Continuous Delivery guidelines from other teams. They’d started from scratch, hit the same problems others had solved, and failed to solve them. It didn’t happen out of ignorance or arrogance. It happened because starting from scratch feels faster. It comes from:

- an illusion of progress

- a bias towards our own ideas

- a fear that learning takes too long

- a desire to prove something (to yourself, or to others)

If the trail is good enough, starting from scratch means more mistakes, duplicated effort, and slower results. You won’t create your own trail through the jungle any faster. You’ll probably end up in a swamp, despite signposts pointing away from it.

And you can always make that trail easier to find, understand, and trust. Capture learnings in easy to consume formats. Share them in existing open spaces that are frequently visited, and searchable. Listen to feedback from teams, collaborate with them on updates, and give them credit for their work.

Don’t start from scratch. Improve what exists, share it back, and leave it better.