“In 2017, a Director of Ops asked me to turn their sysadmins into ‘SRE consultants’. I reminded them of their operability engineering team driving similar practices, and that I was their lead.

In 2018, a CTO at a gaming company told me SRE was better than DevOps, but recruitment was harder. They said they didn’t know much about SRE.

In 2020, I learned of a sysadmin team that were rebranded as an SRE team, received a small pay increase… and then carried on doing the same sysadmin work.

This is for decision makers who have been told SRE will solve their IT problems…”

Steve Smith

TL;DR:

- SRE as a Philosophy means the Site Reliability Engineering principles from Google, and is associated with a lot of valuable ideas and insights.

- SRE as a Cult refers to the marketing of SRE teams, SRE certifications as a panacea for technology problems.

- Some aspects of SRE as a Philosophy are far harder to apply to enterprise organisations than others, such as SRE teams and error budgets.

- Operability needs to be a key focus, not SRE as a Cargo Cult, and SRE as a Philosophy can supply solid ideas for improving operability.

Introduction

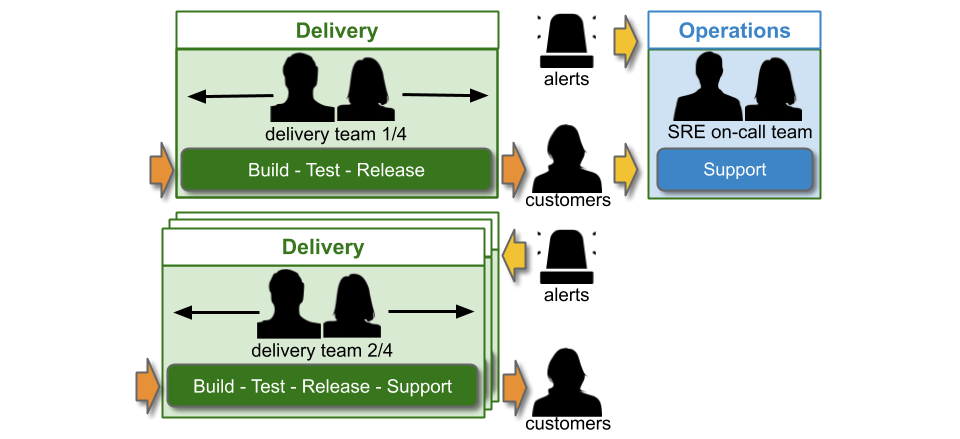

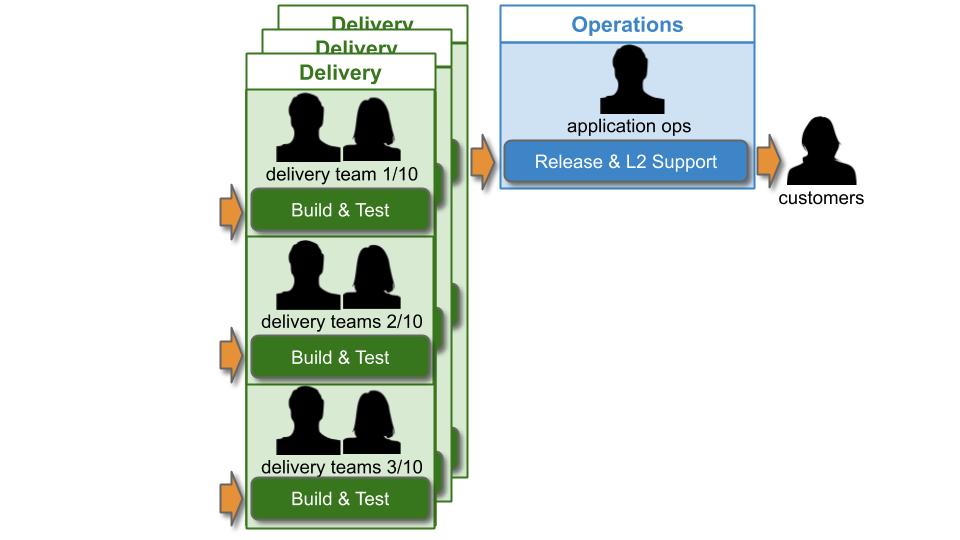

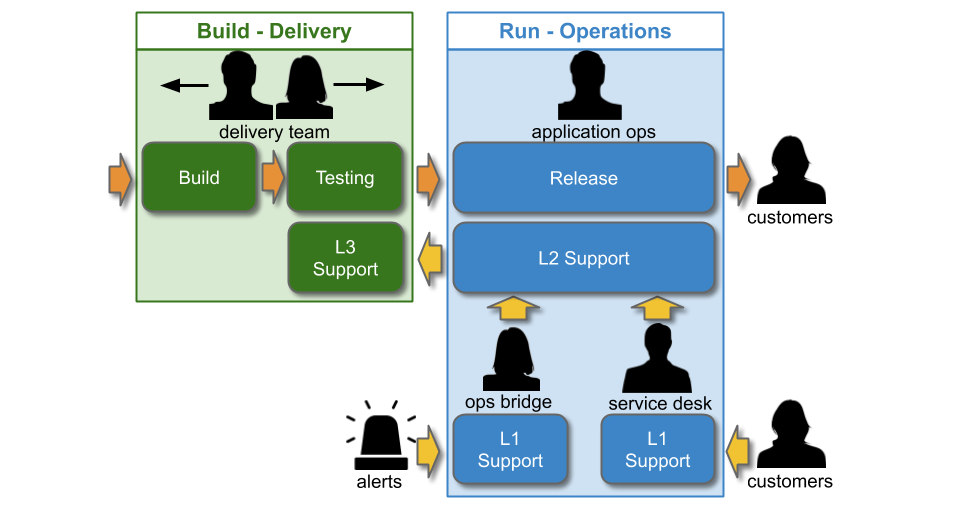

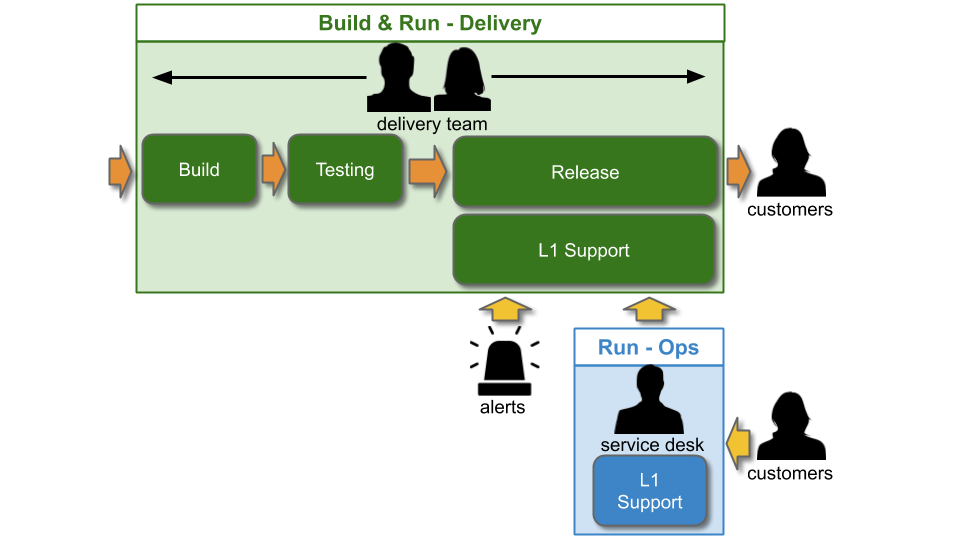

A successful Digital transformation is predicated on a transition from IT as a Cost Centre to IT as a Business Differentiator. An IT cost centre creates segregated Delivery and Operations teams, trapped in an endless conflict between feature speed and service reliability. Delivery wants to maximise deployments, to increase speed. Operations wants to minimise deployments, to increase reliability.

In Accelerate, Dr Nicole Forsgren et al confirm this produces low performance IT, and has negative consequences for profitability, market share, and productivity. Accelerate also demonstrates speed and reliability are not a zero sum game. Investing in both feature speed and service reliability will produce a high performance IT capability that can uncover new product revenue streams.

SRE as a Philosophy

In 2004, Ben Treynor Sloss started an initiative called SRE within Google. He later described SRE as a software engineering approach to IT operations, with developers automating work historically owned outside Google by sysadmins. SRE was disseminated in 2016 by the seminal book Site Reliability Engineering, by Betsey Byers et al. Key concepts include:

- Availability levels.

- Service Level Objectives.

- Error budgets.

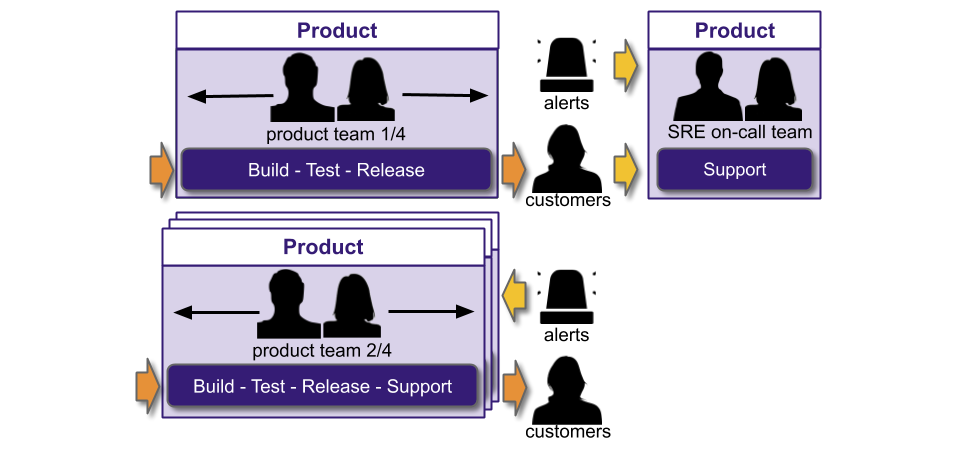

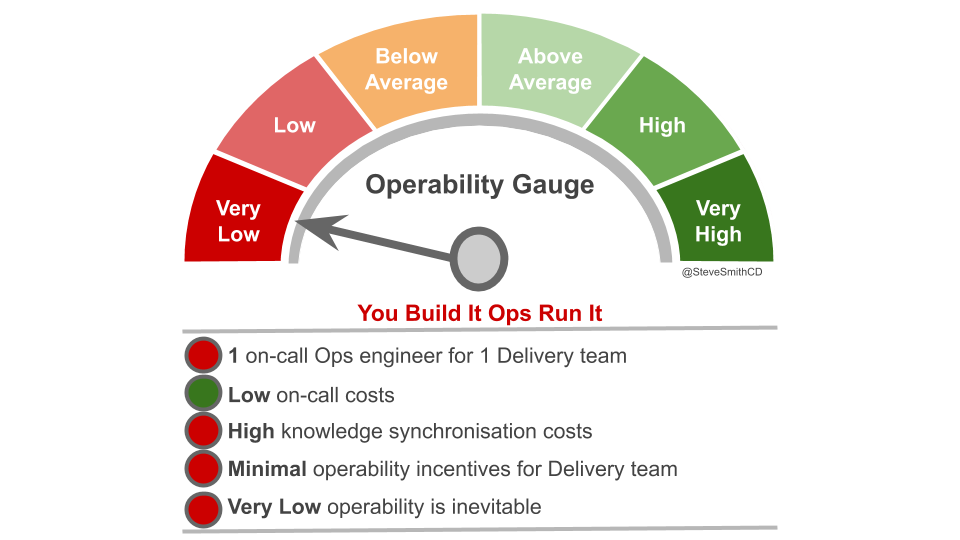

- You Build It SRE Run It.

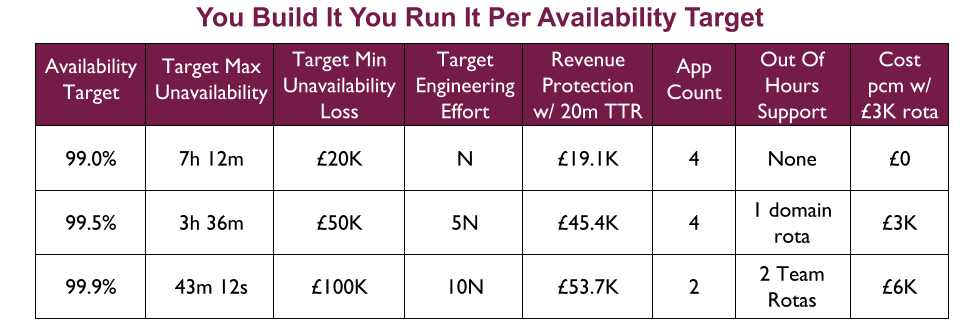

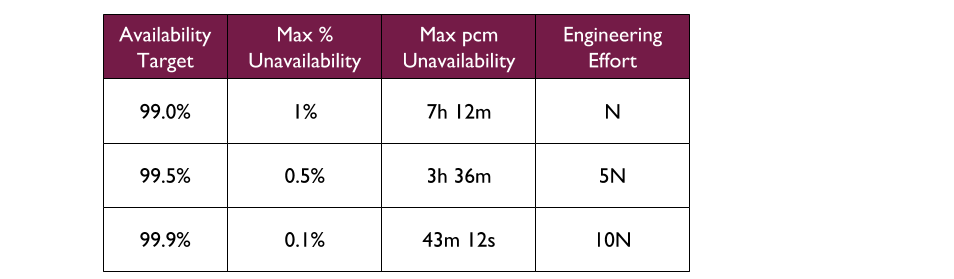

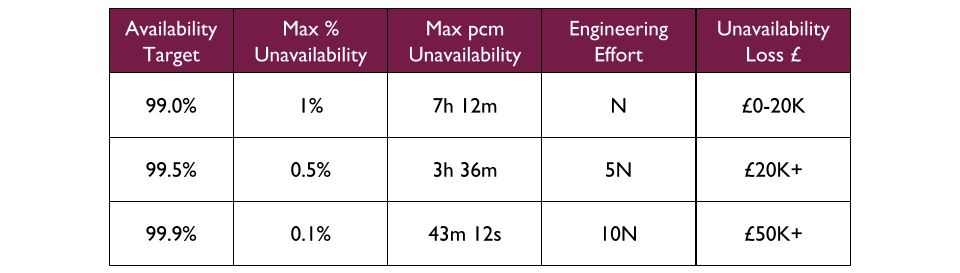

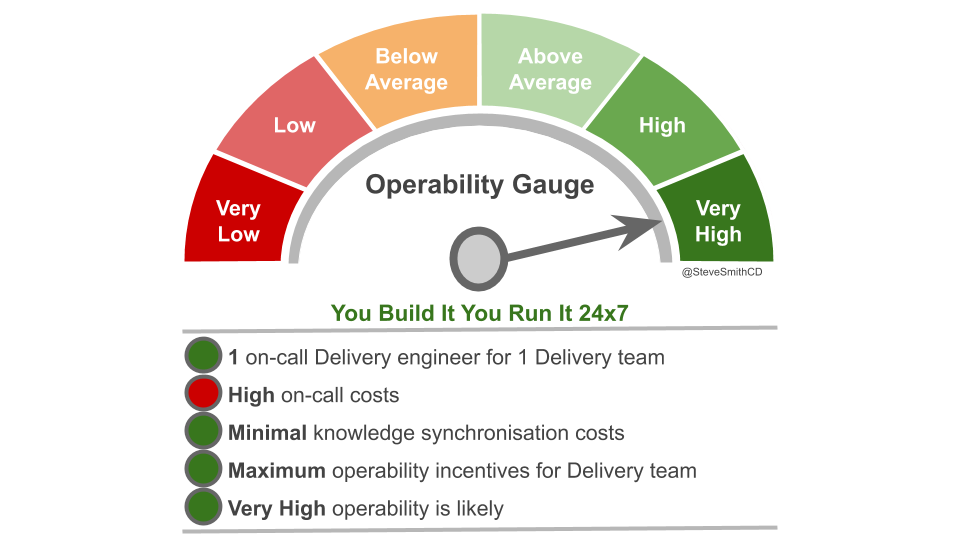

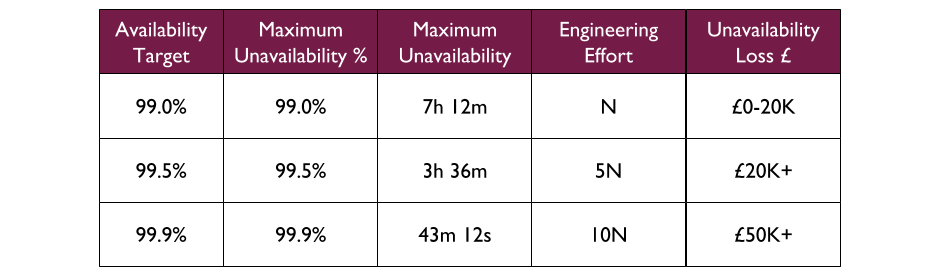

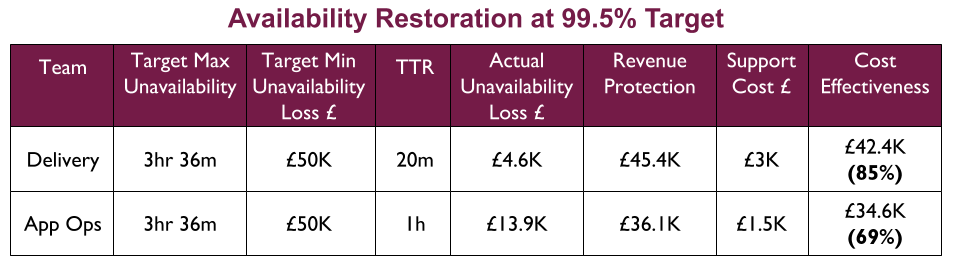

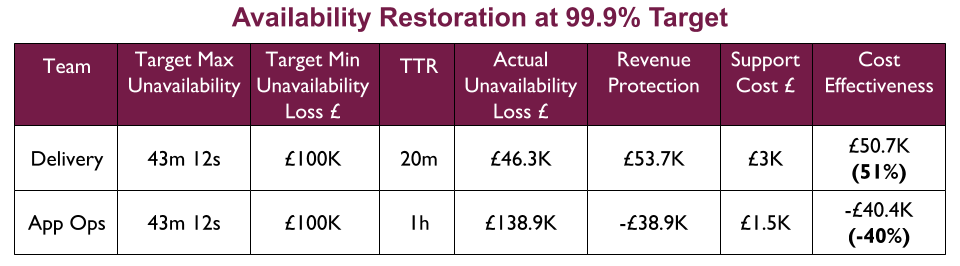

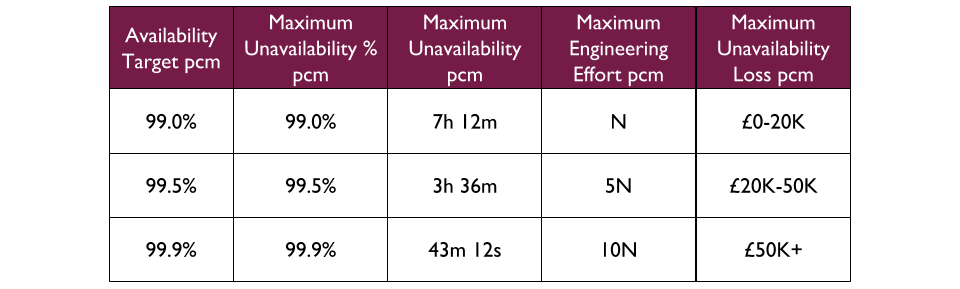

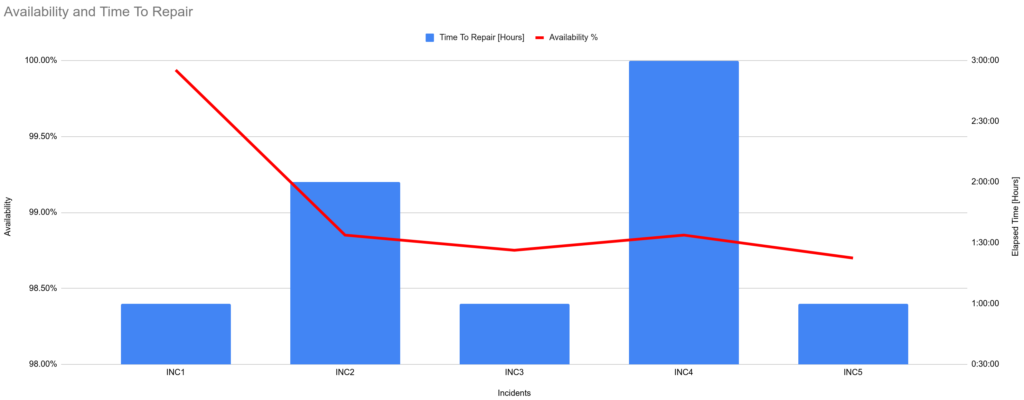

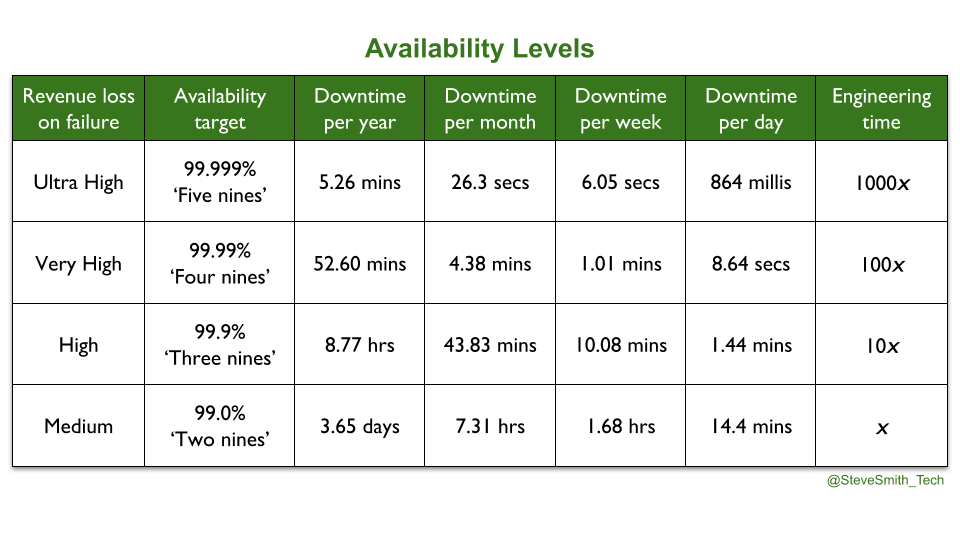

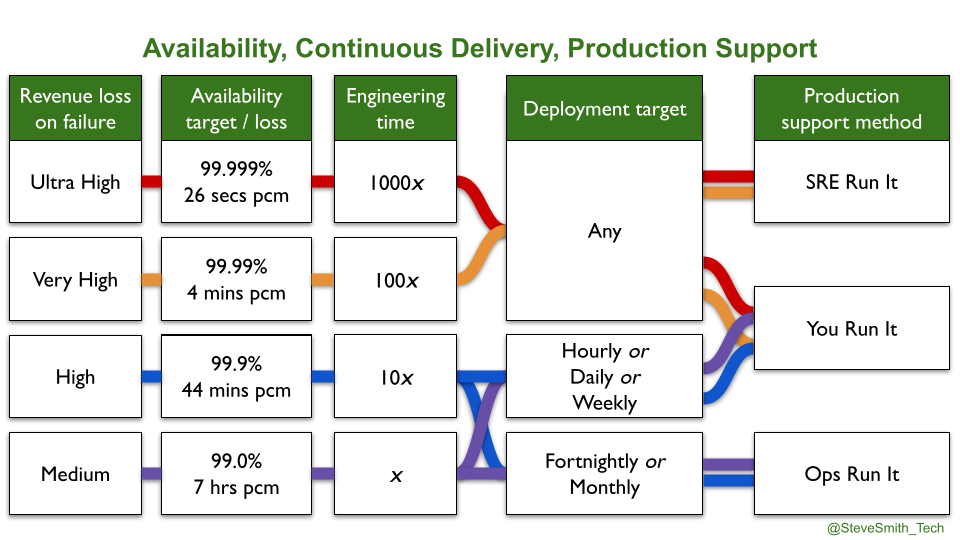

Availability levels are known by the nines of availability. 99.0% is two nines, 99.999% is five nines. 100% availability is unachievable, as less reliable user devices will limit the user experience. 100% is also undesirable, as maximising availability limits speed of feature delivery and increases operational costs. Site Reliability Engineering contains the astute observation that ‘an additional nine of reliability requires an order of magnitude improvement’. At any availability level, an amount of unplanned downtime needs to be tolerated, in order to invest in feature delivery.

A Service Level Objective (SLO) is a published target range of measurements, which sets user expectations on an aspect of service performance. A product manager chooses SLOs, based on their own risk tolerance. They have to balance the engineering cost of meeting an SLO with user needs, the revenue potential of the service, and competitor offerings. An availability SLO could be a median request success rate of 99.9% in 24 hours.

An error budget is a quarterly amount of tolerable, unplanned downtime for a service. It is used to mitigate any inter-team conflicts between product teams and SRE teams, as found in You Build It Ops Run It. It is calculated as 100% minus the chosen nines of availability. For example, an availability level of 99.9% equates to an error budget of 0.01% unsuccessful requests. 0.002% of failing requests in a week would consume 20% of the error budget, and leave 80% for the quarter.

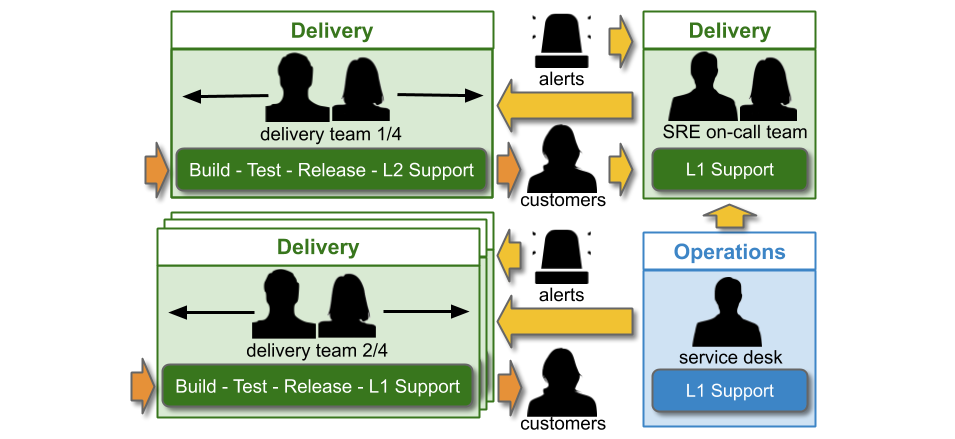

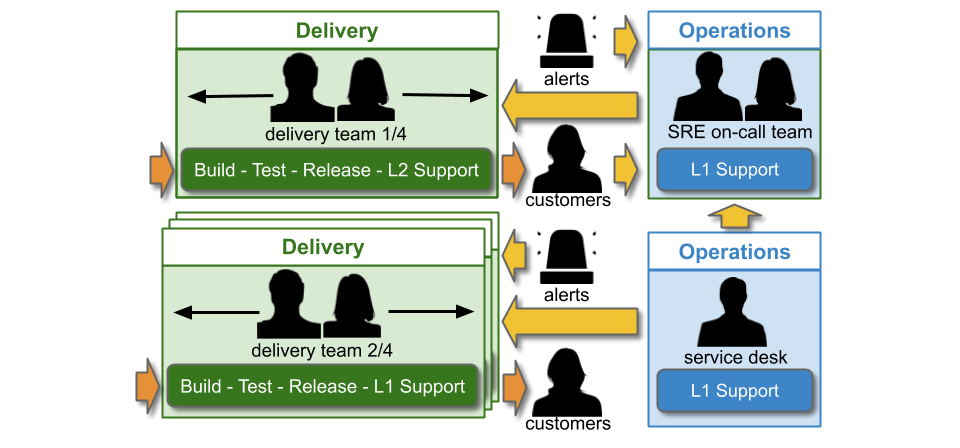

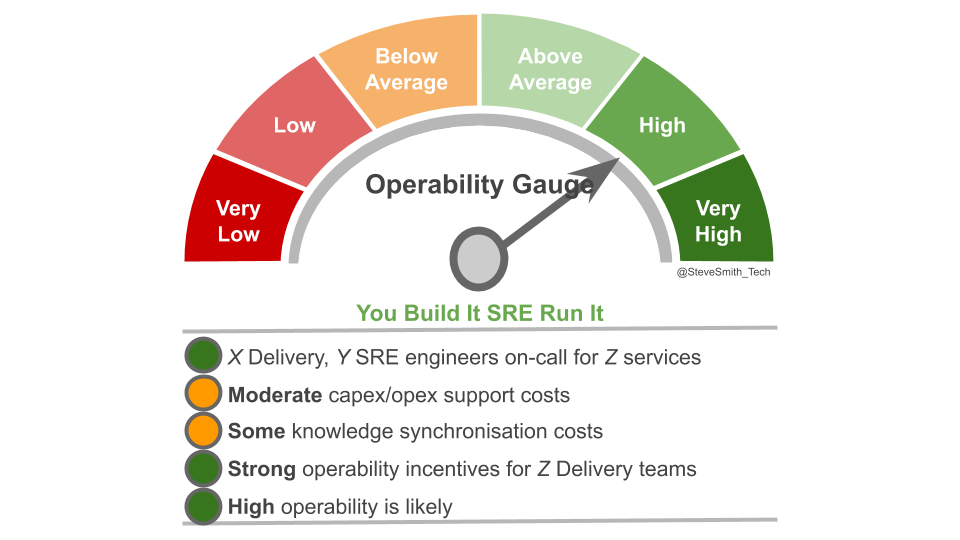

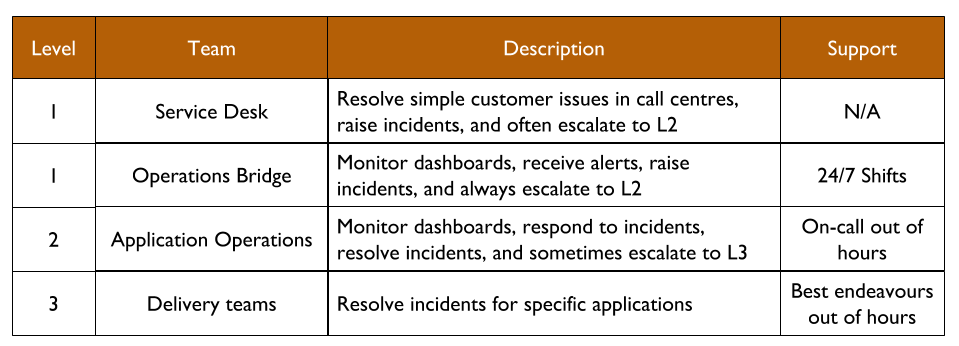

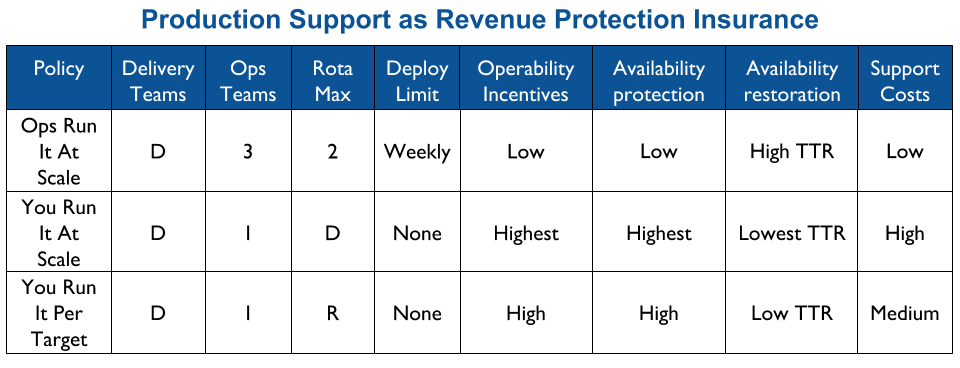

You Build It SRE Run It is a conditional production support method, where a team of SREs support a service for a product team. All product teams do You Build It You Run It by default, and there are strict entry and exit criteria for an SRE team. A service must have a critical level of user traffic, some elevated SLOs, and pass a readiness review. The SREs will take over on-call, and ensure SLOs are consistently met. The product team can launch new features if the service is within its error budget. If not, they cannot deploy until any errors are resolved. If the error budget is repeatedly blown, the SRE team can hand on-call back to the product team, who revert to You Build It You Run It.

This is SRE as a Philosophy. The biggest gift from SRE is a framework for quantifying availability targets and engineering effort, based on product revenue. SRE has also promoted ideas such as measuring partial availability, monitoring the golden signals of a service, building SLO alerts and SLI dashboards from the same telemetry data, and reducing operational toil where possible.

SRE as a Cult

In the 2010s, the DevOps philosophy of collaboration was bastardised by the ubiquitous DevOps as a Cult. Its beliefs are:

- The divide between Delivery and Operations teams is always the constraint in IT performance.

- DevOps automation tools, DevOps engineers, DevOps teams, and/or DevOps certifications are always solutions to that problem.

In a similar vein, the SRE philosophy has been corrupted by SRE as a Cult. The SRE cargo cult is based on the same flawed premise, and espouses SRE error budgets, SRE engineers, SRE teams, and SRE certifications as a panacea. Examples include Patrick Hill stating in Love DevOps? Wait until you meet SRE that ‘SRE removes the conjecture and debate over what can be launched and when’, and the DevOps Institute offering SRE certification.

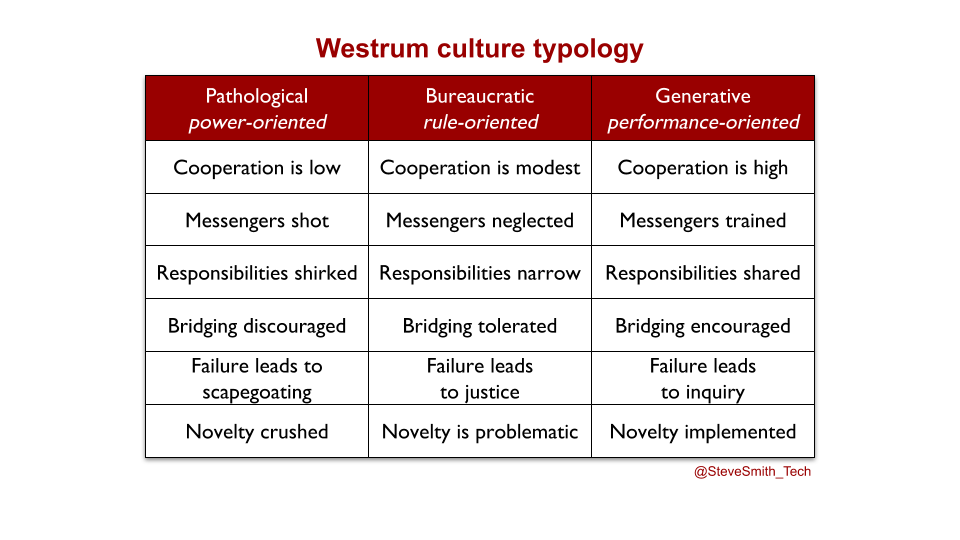

SRE as a Cult ignores the central question facing the SRE philosophy – its applicability to IT as a Cost Centre. SRE originated from talented, opinionated software engineers inside Google, where IT as a Business Differentiator is a core tenet. Using A Typology of Organisational Cultures by Ron Westrum, the Google culture can be described as generative. Accelerate confirms this is predictive of high performance IT, and less employee burnout.

There are fundamental challenges with applying SRE to an IT as a Cost Centre organisation with a bureaucratic or pathological culture. Product, Delivery, and Operations teams will be hindered by orthogonal incentives, funding pressures, and silo rivalries.

For availability levels, if failure leads to scapegoating or justice:

- Heads of Product/Delivery/Operations might not agree 100% reliability is unachievable.

- Heads of Product/Delivery/Operations might not accept an additional nine of reliability means an order of magnitude more engineering effort.

- Heads of Delivery/Operations might not consent to availability levels being owned by product managers.

For Service Level Objectives, if responsibilities are shirked or discouraged:

- Product managers might decline to take on responsibility for service availability.

- Product managers will need help from Delivery teams to uncover user expectations, calculate service revenue potential, and check competitor availability levels.

- Sysadmins might object to developers wiring automated, fine-grained measurements into their own production alerts.

For error budgets, if cooperation is modest or low:

- Product manager/developers/sysadmins might disagree on availability levels and the maths behind error budgets.

- Heads of Product/Development might not accept a block on deployments when an error budget is 0%.

- A Head of Operations might not accept deployments at all hours when an error budget is above 0%.

- Product managers/developers might accuse sysadmins of blocking deployments unnecessarily

- Sysadmins might accuse product managers/developers of jeopardising reliability

- A Head of Operations might arbitrarily block production deployments

- A Head of Development might escalate a block on production deployments

- A Head of Product might override a block on production deployments

For You Build It SRE Run It, if bridging is merely tolerated or discouraged:

- A Head of Operations might not consent to on-call Delivery teams on their opex budget

- A Head of Development might not consent to on-call Delivery teams on their capex budget

- A Head of Operations might be unable to afford months of software engineering training for their sysadmins on an opex budget

- Sysadmins might not want to undergo training, or be rebadged as SREs

- Developers might not want to do on-call for their services, or be rebadged as SREs

- Delivery teams will find it hard to collaborate with an Operations SRE team on errors and incident management

- A Head of Operations might be unable to transfer an unreliable service back to the original Delivery team, if it was disbanded when its capex funding ended

In Site Reliability Engineering, Ben Treynor Sloss identifies SRE recruitment as a significant challenge for Google. Developers are needed that excel in both software engineering and systems administration, which is rare. He counters this by arguing an SRE team is cheaper than an Operations team, as headcount is reduced by task automation. Recruitment challenges will be exacerbated by smaller budgets in IT as a Cost Centre organisations. The touted headcount benefit is absurd, as salary rates are invariably higher for developers than sysadmins.

Aim for Operability, not SRE as a Cult

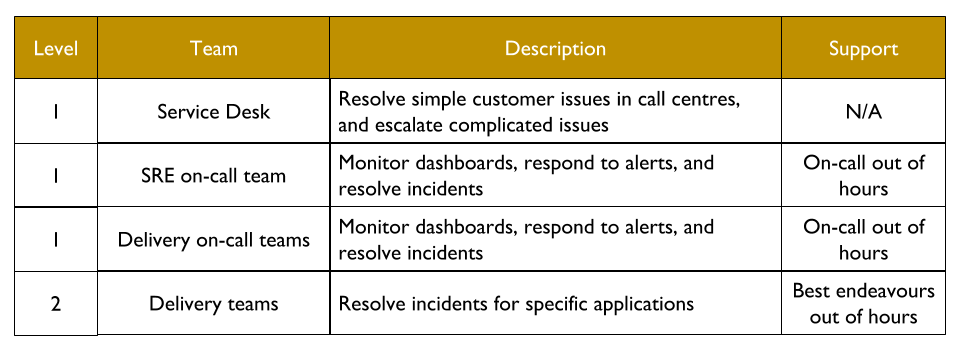

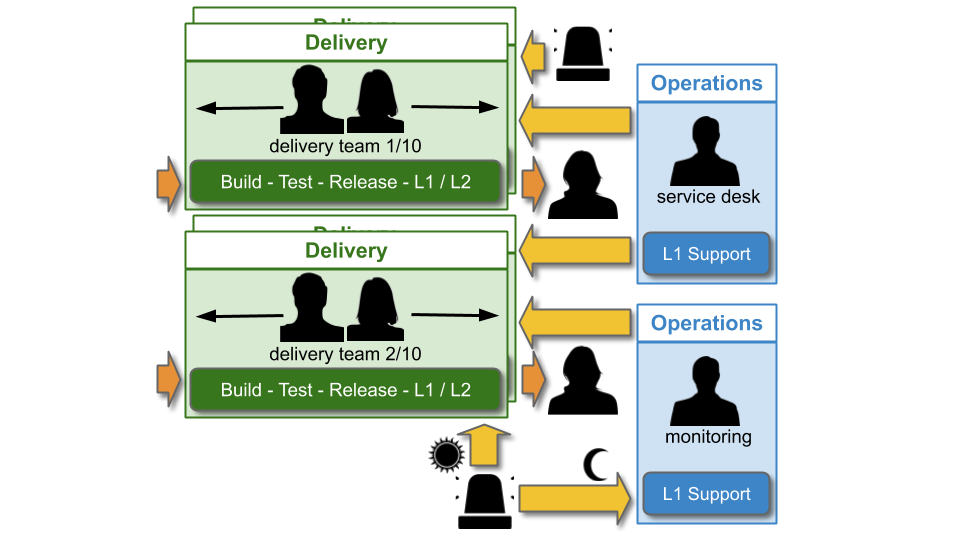

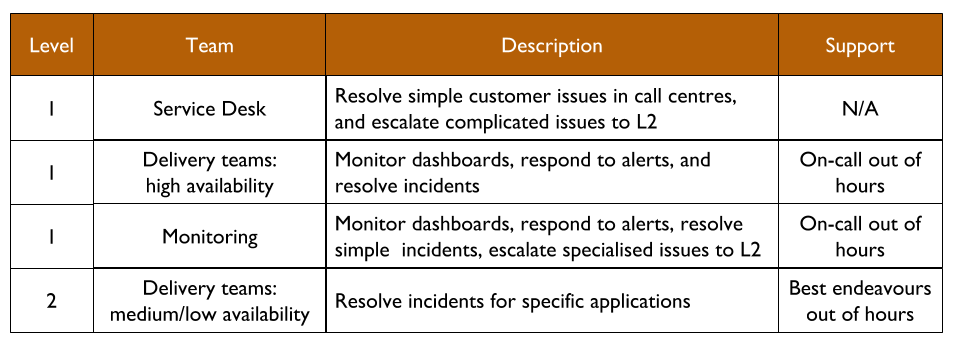

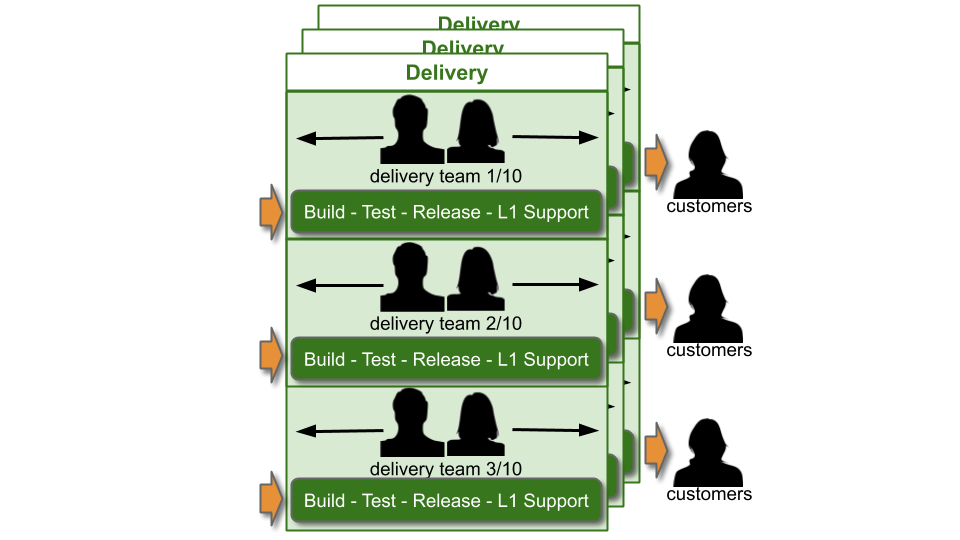

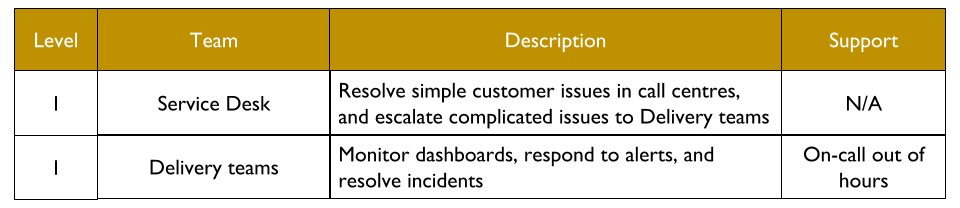

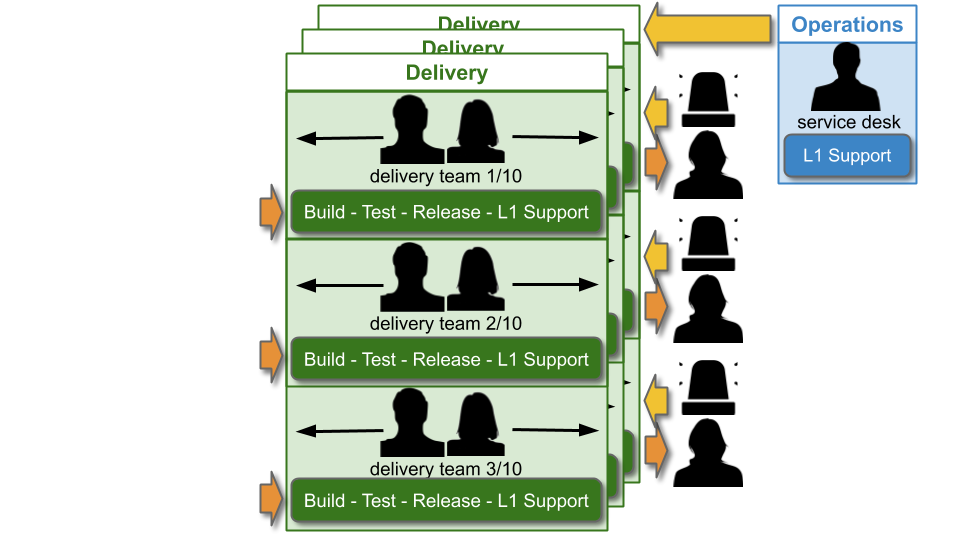

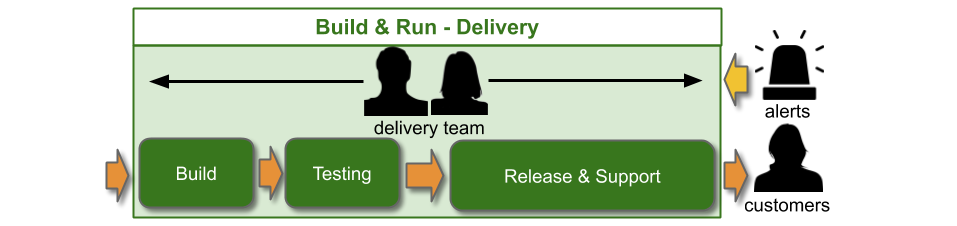

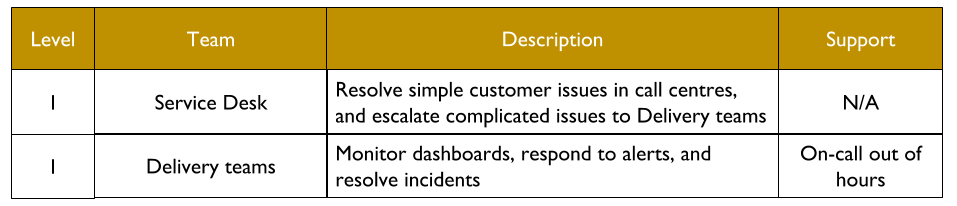

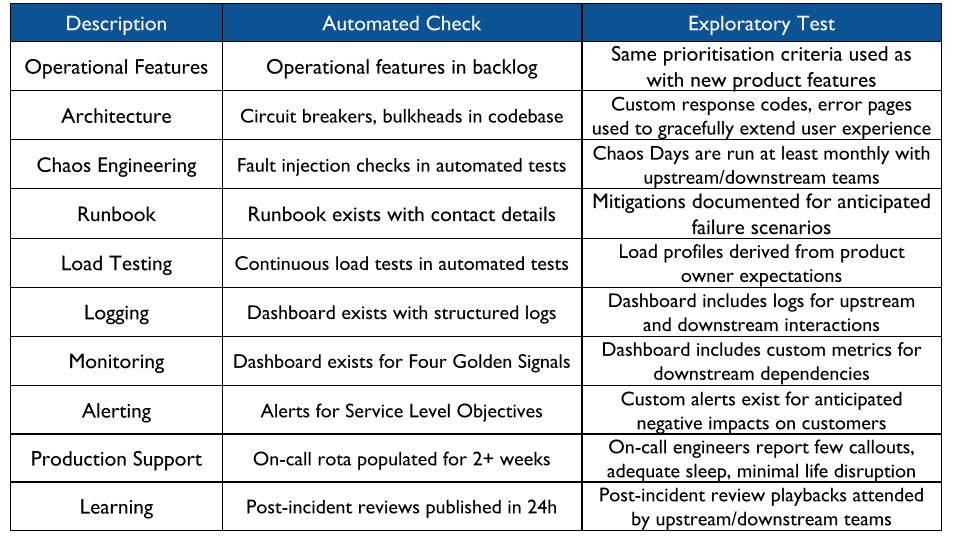

High performance IT requires Continuous Delivery and Operability. Operability refers to the ease of safely and reliably operating production systems. Increasing service operability will improve reliability, reduce operational rework, and increase feature speed. Operability practices include prioritising operational requirements, automated infrastructure, deployment health checks, pervasive telemetry, failure injection, incident swarming, learning from incidents, and You Build It You Run It.

These practices can be implemented with, and without SRE. In addition, some SRE concepts such as availability levels and Service Level Objectives can be implemented independently of SRE. In particular, product managers being responsible for calculating availability levels based on their risk tolerances is often a major step forward from the status quo.

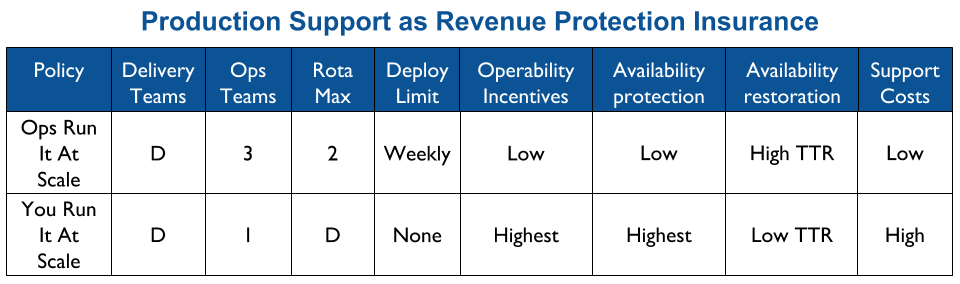

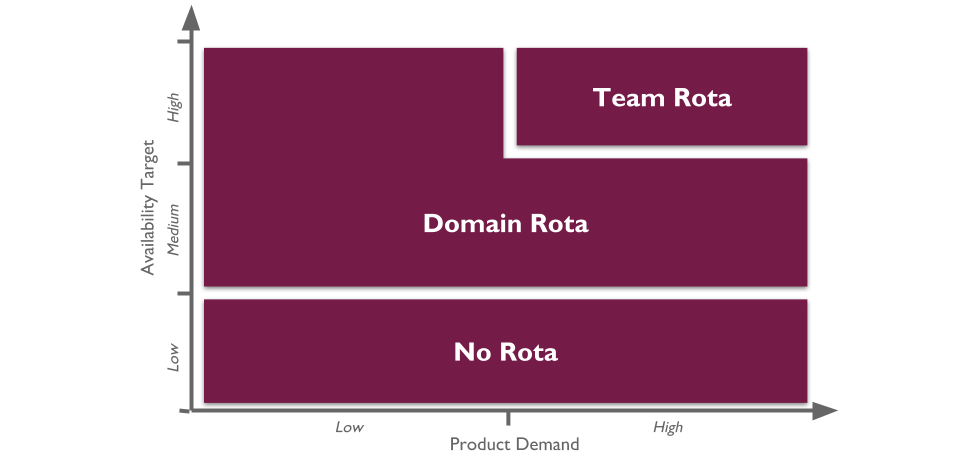

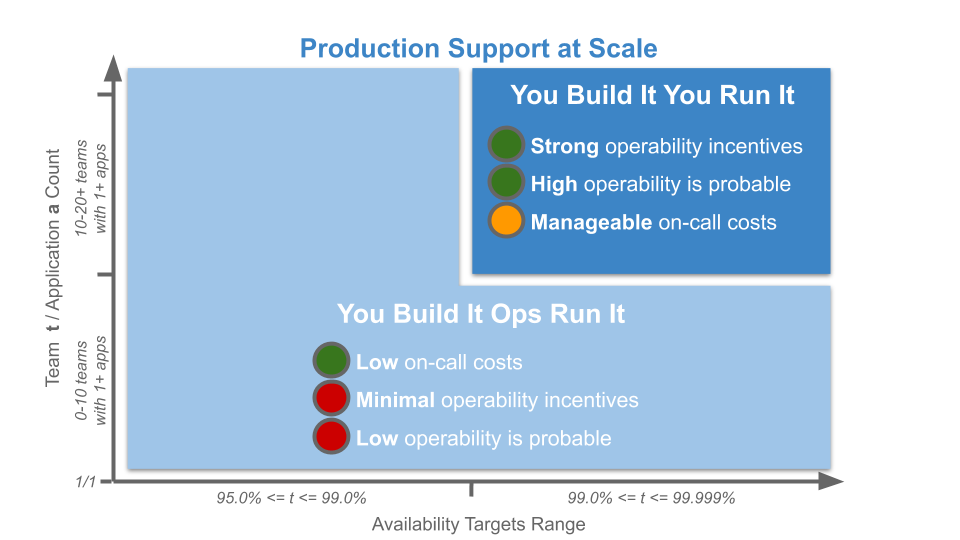

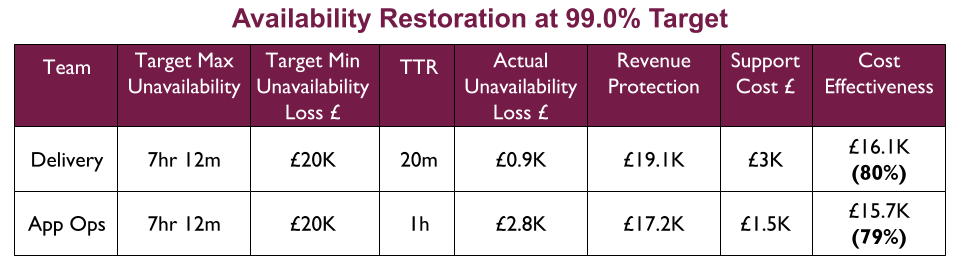

SRE as a Cult obscures important questions about SRE applicability to SMEs and enterprise organisations. You Build It SRE Run It is a difficult fit for an IT as a Cost Centre organisation, and is not cost effective at all availability levels. The amount of investment required in employee training, organisational change, and task automation to run an SRE team alongside You Build It You Run It teams is an order of magnitude more than You Build It You Run It itself. It is only warranted when multiple services exist with critical user traffic, and at an availability level of four nines or more.

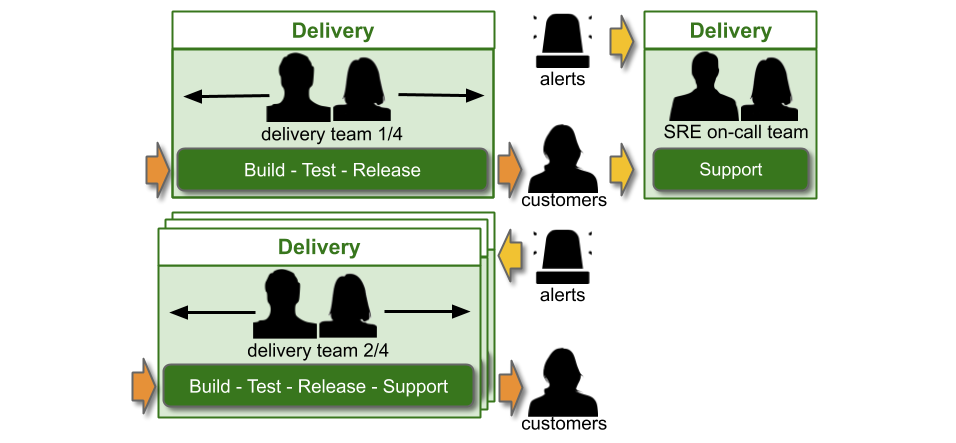

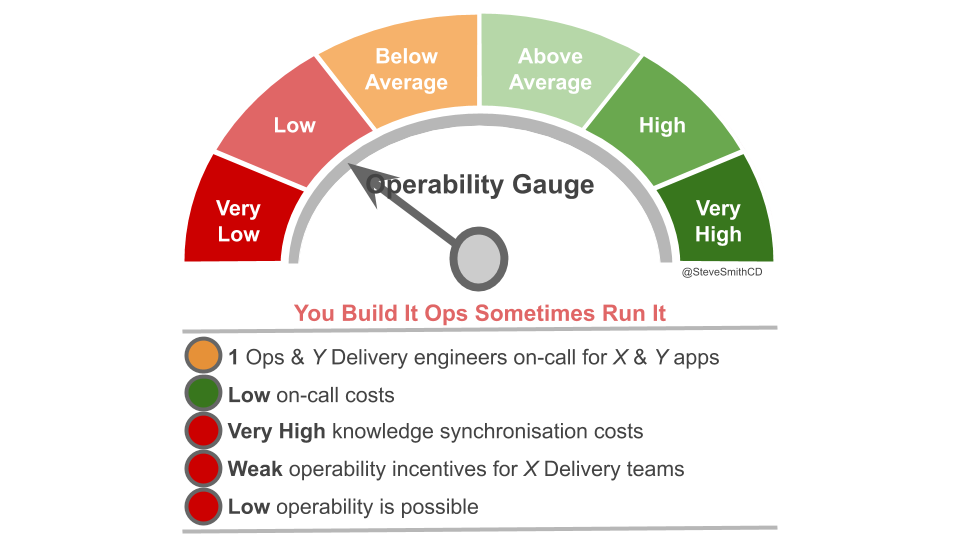

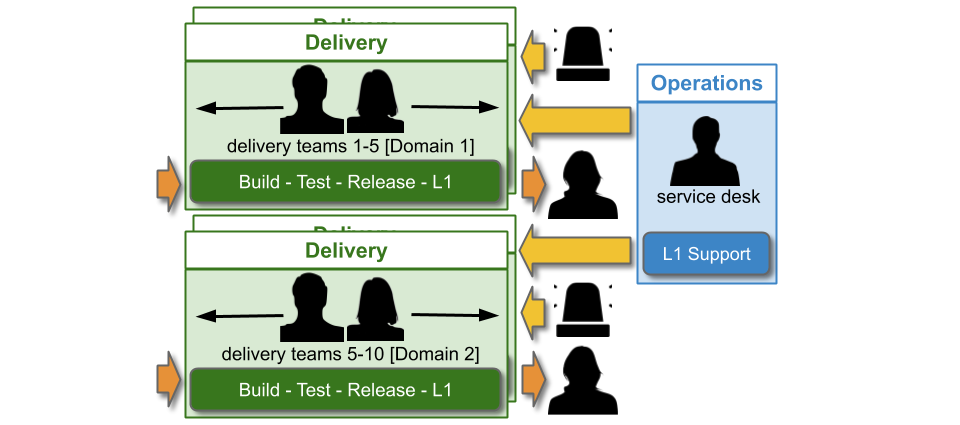

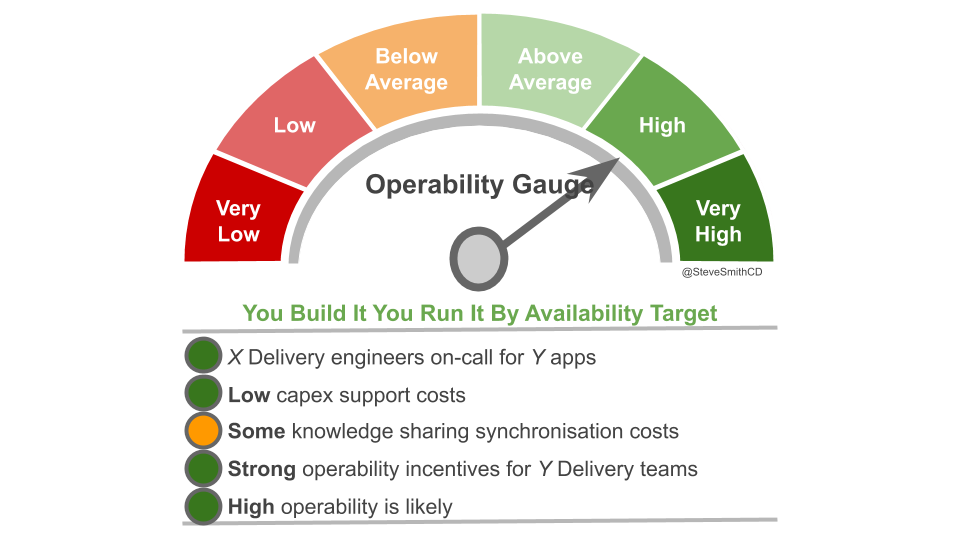

An IT as a Cost Centre organisation would do well to implement You Build It You Run It instead. It unlocks daily deployments, by eliminating handoffs between Delivery and Operations teams. It minimises incident resolution times, via single-level swarming support prioritised ahead of feature development. Furthermore, it maximises incentives for developers to focus on operational features, as they are on-call out of hours themselves. It is a cost effective method of revenue protection, from two nines to five nines of availability.

In some cases, an SME or enterprise organisation will earn tens of millions in product revenues each day, its reliability needs will be extreme, and investing in SRE as a Philosophy could be warranted. Otherwise, heed the perils of SRE as a Cult. As Luke Stone said in Seeking SRE, ‘in the long run, SRE is not going to thrive in your organisation based purely on its current popularity’.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Adam Hansrod, Dave Farley, Denise Yu, John Allspaw, Spike Lindsey, and Thierry de Pauw for their feedback.